The early polymath gets the bisociative worm

Who are you? You might answer that you are an artist, an engineer, a leader, a mother, a husband. Perhaps you graduated at the top of your class, or won an award that you're proud of. Maybe you're the outdoorsy type, or like to cook.

Who are you? Hearing this question, do you feel your pulse rise just a bit? We fear that without an answer to this question we are lost, or that indeed we have lost the game of life. So the answers we give are our experiences, accomplishments, aspirations, and as such these answers defend that we are somehow worthy of being here. They are titles that we've won in our past, or that we're competing to attain and hold on to in the future.

Escaping competition

The gravity of this competition is reenforced first by our parents, then by our teachers, and in perpetuity by our peers. Many of us have had someone in our lives telling us we need to work hard to succeed—sometimes well into our successes.

When our work and our lives day in and day out become as serious as all this, we can start to optimize for outcompeting others. When no direct competition is to be had, we may even invent nemeses against which we can prevail, turning those who would otherwise be friendly into threats in our minds. In the worst cases, we might undermine others, taking opportunities to get ahead by getting them to fall behind.

We can be so easily fooled into thinking these moments in our lives are zero-sum games. If my coworker receives praise, I won't. If my younger sibling starts a family before me, I'm too slow. In turn, we begin to focus more energy on these areas to edge out others, even if we were already on a good trajectory of our own. This mimetic desire sets us off on tangents before we even realize what's happening.

James Carse writes about the value of cooperative over competitive play. In cooperative play, players aim to help each other even when they don't share a common objective. In competitive play, players aim to win. This constant competition can also lead to burnout.

Brené Brown also says that, "When worthiness is a function of productivity, we lose the ability to pump the brakes. The idea of doing something that doesn't add to the bottom line provokes stress and anxiety."

Finally, Allen Pike writes that "The point here is not to add another todo to your pile: oh great, now I need to do all my stuff, and I need to play too?! The point is that we should support ourselves and others in play. We should appreciate the value of goofing off."

When we spend our energy making ourselves better relative to others coupled with an abject fear of failure or falling behind, we leave no space for bettering ourselves because we want to. To grow as people, we need to grow our own awareness and our own understanding, and this comes through a mindblowing process scientists call "trying new stuff."

It's okay to try something new. It may very well turn out to be utter garbage. And that's fantastic because it's still your utter garbage.

Embracing failure

In fields where failure results in rather immediate or dire consequences it has, for some time, been a practice to examine failure carefully when it arises, because failure presents learning opportunities that help us avoid failing the same way in the future. And although it may sound funny, we don't always embrace failure this way when the stakes are low. You give up drawing because you can't draw noses, so you have a stack of 37 sketches of Voldemort. After burning another pan of food you decide takeout is just easier from now on. Because the stakes are low in either direction, we naturally settle into the paths with the least friction. We revert to comfort.

Sometimes the friction is so great it prevents us from getting started in the first place. We think about the likelihood something great will happen, determine that it's some number near zero, and figure it isn't worth the effort. This act of self-filtering is itself a failure, because it cuts off so many possible paths we could travel before we ever look down them.

If you imagine the infinity of possible universes before you, also imagine that any filtering you do smites some untold thousands of those realities. When you open yourself to the possibility of failure, some of these universes pop back into existence.

We sometimes fight this infinity of possibilities thinking that we can identify and plan toward some golden path through it; this again comes from that competitive attitude. Carse writes, "To be prepared against surprise is to be trained. To be prepared for surprise is to be educated."

Now, building a rapport with failure is a gentle exercise; small perturbations in our experience can easily topple the carefully constructed boundaries of safety we build. One misplaced chastisement for an honest mistake can level us, especially early on. Here is where learning from failure becomes so important. Were we only to accept failure but learn nothing, we'd be condemned to repeat it without progress. When we take the time to understand the circumstances that lead to failure, something that was once to be feared becomes plain and quite surmountable.

If we can escape the fear of failure, we also escape the possibility that confronting new information will cause us to recede, to hide, to reject. Confirmation bias and the backfire effect are perhaps the biggest scourges on modern discourse, and are propped up in large part by the fear of failure and the consistency bias that arises from it. People who fear change want to hold so tightly to what they believe that they may never know anything better.

Shedding the constraint of failure allows us to try the same things in new ways with better outcomes, which can produce a virtuous cycle. And when this cycle really gets going we may start to venture into trying new things altogether.

Exposure

Think about whether you would describe yourself as a specialist.

Think about whether you would instead describe yourself as a generalist.

Perhaps you fluctuate between these two states regularly, or take the "T-shaped people" approach.

Deeply specializing in something is commendable, and shows I think a particular familiarity with failure; we can't deeply embed ourselves in a practice without regular visits with failure. But no matter your place on the specialist/generalist spectrum, I propose that you should increase your exposure to new things.

I want to pause here to state that methods of exposure in practice are sometimes hard to identify and incorporate, and can require a certain level of privilege. It's difficult to worry about exposure to new things when faced with pressures toward finances, gender, race, ability, or education. Although you can try many things without needing to pay money or find a lot of time, psychological safety is an absolutely essential underpinning. Seek to contribute to others' psychological safety on your path if you wish to see them thrive.

Removing self-filtering is a big part of exposure; don't limit what you're exposed to prematurely. But self-filtering happens only with whatever you might already be exposed to naturally. We need to actively seek out methods of increasing this natural surface area if we are to get the kind of exposure I'm talking about.

A common approach to this exposure is travel. Traveling even within your own country can expose you to geological, political, economic, and culinary diversity. Traveling, especially internationally, can expose you to even more of the same, with the added facet of language. Although it can be a powerful gateway and motivator, travel tends not to have a lasting effect because it lacks immersion—once you go home, you're only exposed to the echoes you can retain from the experience. Exposure is best when repeated and sustained.

I find that speaking with people, listening to people, reading what people have to say goes a very long way. Being exposed passively and casually, on a regular basis, to what and how other people think is a rich place to grow. Surround yourself with people from all walks, and be highly open to being changed by what they have to say.

Another method for exposure is to find hobbies, and find ways to work at them that satisfy you. And I do mean satisfy you. You might hear me saying "get a side gig" but I absolutely do not mean that. Do something because you find it fun, engaging, fulfilling. Do it because you're exposing yourself to new things. Don't do it to be productive.

I've tried turning some of my hobbies into side gigs, and I inevitably grow to resent the situation because it adds expectation to what is meant to be enjoyed; it takes me some time after removing myself from these situations to revisit those particular hobbies again.

Find things you can learn the core of and can slowly branch out from over time, giving yourself time to learn the concepts without having to delve all the way into them.

Something perhaps counterintuitive happens as you gain exposure to more and more ideas and concepts; many things you thought were disparate are in fact highly similar. The "obvious" differences you saw on the surface turn out to be backed by fundamentals that remain stable across a wide swath of situations. These fundamentals start to pop up over and over again until you realize that most things aren't as scary as you thought they were, but instead riff on familiar themes you can use as a safety net as you learn more about the nuances of the space.

Exposure to creativity also breeds more creativity; placing yourself in an already creative environment and the practice of "starting from abundance" have positive impact on our ability to think and our openness to abstract thought.

I want to give a sense of scale on trying new things by saying a little bit about what I've done personally. I consider myself a generalist, but know that I may even be somewhere in the middle of the spectrum, so what I'm about to say could even be considered a lower bound:

- Professionally, I've tried the fields of remote sensing technology, personalized medicine, B2C marketing, and academic publishing.

- In software I've tried C, C++, MATLAB, Ruby, Python, and JavaScript in addition to a host of markup languages.

- Aside from programming languages, I like natural languages too! Beyond being a native English speaker, I've tried Spanish, Mandarin Chinese, Japanese, French, and German.

- In addition to writing software, I've tried writing poetry, blog posts, songs, and books.

- In music, I've tried saxophone, piano, trombone, trumpet, guitar, bass guitar, and voice.

- In the arts I've tried drawing, painting, acting, improv, pottery, digital art, woodworking, and photography.

- In photography I've tried architecture, portraiture, fashion, food, and weddings.

- In sports I've tried soccer, basketball, football, track, skiing, snowboarding, and ballroom dancing.

- In the kitchen I've tried pickling, sourdough baking, sous vide, and countless recipes from all sorts of cuisines.

I've experienced failure in all of these things to varying degrees, but I don't feel as though I've failed them or failed at them. Although I haven't stuck with all of them, it isn't because I feel I'm absolutely done with any of them. I feel instead that I could greet any one of them warmly, like picking up conversation with a close friend after so many years.

So, it isn't that I mean pick up one new thing to try. Starting there is good. But try trying more new things than the day before

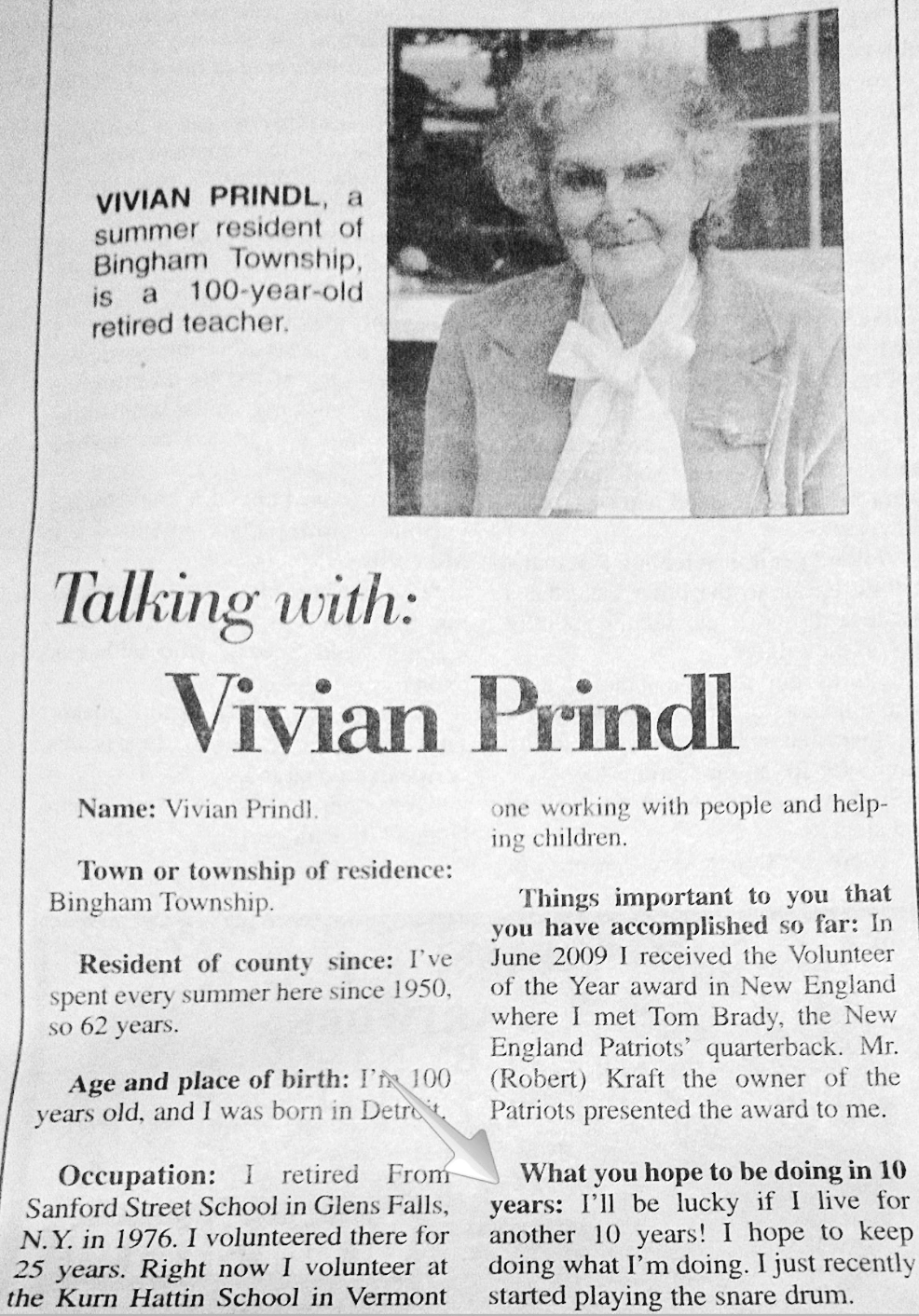

I found this picture I took from my local newspaper quite a few years ago, where Vivian, 100 at the time, had just started learning to play the snare drum.

I love this example because she is so self-aware in the most positive way.

It's also important to understand this collection of hobbies I mention spans many years and they aren't all happening simultaneously. Even then, they can be a lot to manage, and I've definitely ebbed and flowed in response to other constraints on my time. But as you broaden your exposure you might find that those familiar fundamentals across domains help keep things manageable more than you might think.

I believe this has something to do with the uniquely human capability of abstract symbolic reasoning. Abstract symbolic reasoning is one of the most powerful pieces of human cognition. It means that we can observe concrete phenomena in our environment and slowly turn those into conceptual representations that generalize to other phenomena we haven't encountered before. We can adapt to new situations because they look like situations we've seen in the past. We can also layer this conceptual understanding to create more sophisticated models of the world.

As we're exposed to more ideas, our symbolic representations of the world grow richer and deeper. We may start to make connections we can't quite articulate but that help us make leaps we never thought we could. It's in this way that we start reaching a kind of critical mass toward innovation.

Innovation

Even though we have the power of abstract symbolic reasoning, and even though we can describe some of our thought processes, the brain operates over a kind of "meaning space" that we don't fully understand. We can identify and name certain extractions of this meaning space, but our brain is processing things more deeply and powerfully than we can see or describe. As we incorporate new information into this meaning space our ability to connect ideas grows at a rate much higher than linear.

Innovation is the synthesis of concepts that, up until now, have seemed disparate. Innovations may prompt someone to ask, "Why didn't I think of that?" and usually the answer is that it was indeed hard to think of. Not because of a lack of intelligence or an oversight, but because no one had adjusted the pieces to fit together until that moment.

It follows then that it should not and cannot be a goal to "innovate"—to truly innovate is not something you can arrive at through hard work alone. It requires putting in the slow, meaningful effort so that something can finally coalesce into a critical mass.

Sometimes these things seem so intuitive in retrospect, but are often such a long time coming. It's like the phrase "overnight success"—it's often backed by a long period of toil and, if you're not careful, periods of shirking your other responsibilities. These so-called "Eureka!" moments come barging in when someone has finally had the perfect confluence of exposures to lift the veil to some new magic. Perhaps poetically, "Eureka" shares its etymology with the word "heuristic" which describes a method of problem solving based on experience and observation. And this can happen anywhere, to anyone, at any time. This may be why a great many inventions have been accidentally discovered while the inventor was pursuing some other goal, or no goal at all.

Some research is also supporting that walking idly is one of the best ways to let your brain work on connecting the dots. This has also been shown anecdotally well back, and my favorite example is when William Rowan Hamilton, who had been trying to find a new superset of complex numbers, suddenly found his inspiration while out on a walk in Dublin in 1843. Not wanting to forget the formula, he etched it into the stone of a nearby bridge. The math that he worked on would go on to be incredibly important in rendering 3D graphics some 150 years later.

So, to wrap this up: Innovation is valuable but doesn't just spring out of hard work alone. Innovation arises from synthesis of things that were once disparate, and it's increased exposure to ideas that increases the chances of finding things to synthesize. Trying new things without fear of failure or a specific desire to "win" them creates a positive process around exposure. And letting go of our competitive nature makes room for trying new things.

As you try new things, take in the structure before taking in the specifics; see the familiar fundamentals underpinning the space so you can confidently explore the newness. And if you desire to do great things, you must first shed the desire to do great things. And if you do not desire to do great things, you may just do them yet. Perhaps you already are.